Home » Uncategorized

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Stitching and History

June 12, 2020 Update

I’ve been searching for examples, reading and taking notes. I’ve also decided on a design and pieced it together. I need to finish a gift project before I trace this one and start it.

I also have the start of a bibliography. I will update it as I find more sources.

Initial Post

This will be where I post updates on my summer research and stitching project on antislavery needlework. I’m picking up a project I started back in 2013, which you can read here. Since writing this, I’ve found quite a bit more material on antislavery needlework and bazaars and I’ve also learned to embroider. As I expand and revise the original conference paper, I will be designing and stitching a sampler with an antislavery motif. I am taking my inspiration from this sampler in the Philadelphia Museum of Art collections, created by British activist Hannah Bloor.

The design for my sample will feature the female version of the Wedgewood medallion. I will be choosing a quote or other text to put on the sampler. Right now I am leaning towards a quote from Sojourner Truth.

On the scholarly side, I am building my bibliography and reading through new secondary sources and scouring my archival notes for more primary source material. In the upcoming weeks I will post my reading list.

Teaching Writing in a History Class

If your state is anything like mine, most of your students arrive in their college classes having done very little structured writing in high school. They know how to take a standardized test but writing an essay is something they have had little practice at since middle school.

I find myself teaching argumentative essay skills in my freshmen level survey courses every semester. I am not trained as a composition teacher but here is how I do it.

Structure is Key

Most of us over the age of 30 learned to write the five paragraph expository essay in middle school and wrote several of them every year after that. My current students might have learned the model but have had little practice. I show them both an example of a five paragraph history essay (I usually use a student’s A paper from the previous semester) and an outline of how the introduction, body paragraph and conclusion are organized. This outline from Bucks County Community College is similar to the one I use. I explain how the sample essay meets all of the parts of the assignment and rubric (has a clear thesis, uses primary sources to support that thesis, explains how those examples support the argument, cites the sources properly, and contains few or no grammatical errors).

Assignment

I give students short (3-5) page paper assignments based on a set of 4-5 primary sources, a lecture or two and a textbook chapter. After reading the material, students are first asked to choose from one of three sets of questions guiding their topic.

Students the identify 3-5 examples from the primary sources (usually quotes of 1-2 sentences each) that speak to their topic. Once the evidence has been collected, they sort it into three subtopics. They then draft their thesis statement by rephrasing the questions they have chosen into a single sentence with a three part response. Students are encouraged to fill in the outline with their evidence before they begin writing.

From this point, the structure of the paper is very clear so students can focus on working on clear writing and analysis of their sources.

Proofreading and Revising

I also provide students with a checklist of things to ensure they are not making common writing errors and grammatical mistakes. The checklist I use was developed by a colleague so I am not able to share it but it covers things like page numbers and formatting, common grammar and spelling errors, citation errors, and asking them to confirm that each body paragraph supports their argument and each example is fully analyzed (meets the “so what” test).

Teaching Undergraduate Research Seminars

For those faculty teaching undergraduate senior thesis or research seminars, finding material to help students navigate things academics do as second nature can be difficult. Here are some of my favorite resources. In addition to assigning students to read sections of Turabian’s Guide and Strunk and White, I’ve found these online resources helpful and accessible.

Choosing a Topic

Ben Franklin’s World Episode 66: How Historians Choose a Topic

Writing a Prospectus

Finding Sources

Primary source collections like those published by Women and Social Movements make great starting points for students. They contain documents, an introduction written by a historian and a bibliography. If your library doesn’t have a subscription to the database (or your students aren’t interested in gender history), you can find other sets like these but without the nice introduction at the Digital Public Library of America in their primary source sets. When my students get really stuck, I’ve put together sets of 5-10 documents and a couple of books and articles to get them started.

Students can also search historical newspapers at Google Newspaper Archives (sadly no longer being developed).

For secondary source searches, your university librarians probably teach classes on searching databases and the catalog. I also give my students a quick and dirty introduction to how to use JSTOR and Academic Search Complete like a historian.

Analyzing Sources

Doing History Podcast Episode on How to Read Historical Sources

Managing Sources

I use Zotero to manage my own research material and I find students find is easier to use than a lot of other systems. It is particularly useful because it does a good job formatting Chicago style footnotes.

The Water Cure and Self Care

I recently went to the annual meeting of the Berkshire Conference of Women Historians which was held at the Gideon Putnam Hotel on the grounds of Saratoga Springs State Park. The meetings are three days of networking, conversations about the academy and history, research and teaching, and a lot of catching up with friends. If you identify as female and are a historian (in the academy or outside of it), I highly recommend joining the organization.

Attending the meeting in Saratoga Springs meant I had the opportunity to experience the springs themselves, a location that was frequently visited by the Everett family, who figure prominently in my newest research project. The Everetts were Welsh immigrants who settled in Remsen, New York and were active participants in a number of reform efforts. The family took several trips to Ballston Spa and took the water cure or hydrotherapy. Several members of the family had chronically poor health and they were believers in homeopathy and dabbled in Grahamism. Mary Everett eventually attended medical school and practiced homeopathic medicine in New York.

Attending the meeting in Saratoga Springs meant I had the opportunity to experience the springs themselves, a location that was frequently visited by the Everett family, who figure prominently in my newest research project. The Everetts were Welsh immigrants who settled in Remsen, New York and were active participants in a number of reform efforts. The family took several trips to Ballston Spa and took the water cure or hydrotherapy. Several members of the family had chronically poor health and they were believers in homeopathy and dabbled in Grahamism. Mary Everett eventually attended medical school and practiced homeopathic medicine in New York.

Taking the ‘water cure’ or hydrotherapy at a spa town meant traveling to stay at a boarding house or hotel in the town and spending several hours each day drinking, bathing, or lying wrapped in wet cloths in order to purge illness from the body with mineral water. Ballston Spa and Saratoga Springs were popular destinations for taking the water cure as they were close to the New York capital region, accessible by train by the 1830s, and there were large hotels for wealthy clients to stay in relative comfort.

Part of the allure of the water cure was the progressive atmosphere of the spa towns, which attracted middle-class tourists from New York City and Albany. While days were spent taking the waters and walking the shaded paths in the woods, evenings were filled with lectures by homeopathic medical practitioners, antislavery activists, dress reformers, scientists and researchers. The hotel and boarding house dining rooms served meals designed to meet the requirements of special diets designed by Sylvester Graham, inventor of the Graham cracker and diet reformer who advocated a bland, vegetarian diet and abstention from alcohol as a way to ensure or restore health.1Elaine G. Breslaw, Lotions, Potions, Pills, and Magic: Health Care in Early America. New York: NYU Press, 2012. pp. 159-64

After the Civil War, physician Simon Baruch advocated bathing as an essential part of good health, and worked with the state of New York to provide public baths for working class residents of New York City as well as conducted research on the medical benefits of the mineral baths at Saratoga Springs.2Patricia Spain Ward, Simon Baruch: Rebel in the Ranks of Medicine, 1840-1921. (Tuscaloosa:University of Alabama Press, 1994)

After the Civil War, physician Simon Baruch advocated bathing as an essential part of good health, and worked with the state of New York to provide public baths for working class residents of New York City as well as conducted research on the medical benefits of the mineral baths at Saratoga Springs.2Patricia Spain Ward, Simon Baruch: Rebel in the Ranks of Medicine, 1840-1921. (Tuscaloosa:University of Alabama Press, 1994)

The spa that stands in Saratoga Spa State Park today is not the same spa complex that the Everetts would have visited. The complex that makes up a large part of the park was constructed in the 1930s as part of state efforts during Reconstruction, but some of the early nineteenth century taps remain publicly available. Unfortunately, none of them were flowing the day that I toured the park, many of them are no longer functioning due to the waters being siphoned off to the bottling plants that were built in the late nineteenth century. The modern bath complex takes up only a tiny portion of the complex, most of the baths are left abandoned behind iron bars.

During one of the breaks in the meetings and talks of the weekend, I “took the waters” in the form of a mineral bath at the modern spa. Unfortunately I don’t have any photos of the spa room, which is original to the 1930s construction and is likely quite similar to the bathing rooms used in the nineteenth century. The room held a tub which was filled with the brownish, slightly effervescent spring waters (which are mixed with warm tap water to make the bath more enjoyable, nineteenth century bathers would have used cold spring water only). The bath experience was a bit strange, the water has an odd odor and you float much more than you would in a regular bath because of the high mineral content of the water.

Floating in the tub for twenty minutes was an interesting experience and gave me some time to reflect on the importance of self-care and the safe space that the spa provided for the early-nineteenth century reformers who are the focus on my work. Much like modern academics, they faced incessant scrutiny and criticism of their work and daily activities. Retreating to the spa to care for their bodies and rest their minds was an important break from the monotony of speaking tours, letter writing campaigns and other reform activities. Taking the time away from writing, teaching, and doing administrative work to catch up with friends, take a walk in the woods, chat with others who value scholarship, diversity and hard work is something we all need to do a little more often.

“The Cause of Education Here”: Cynthia Everett and the American Missionary Association Schools in Norfolk, VA

This paper is a draft and may not be distributed in any form without the permission of the author. Thanks to Rhiannon Williams, University of South Wales for information on the Everett family, Louis Humphrey for his assistance in transcribing Cynthia Everett’s papers, and Troy Valos and the staff of the Sargent Collection, Norfolk Public Library for their aid in locating the schools run by the AMA in Norfolk.

In 1869, a 28-year-old schoolteacher from upstate New York was sent by the American Missionary Association to Norfolk, VA to teach for the schools established for African American children after the Civil War. Although from a family that had strongly supported antislavery efforts before the war, Cynthia Everett had had little exposure to African American culture or southern society before her move to Norfolk in the fall of 1869. She spent most of two years in Norfolk and Charleston, SC, and her letters reveal the details of daily life in Reconstruction-era southern cities and the negotiations over the role of northern, white women in the leadership of local school systems and the networks of charitable organizations which tried to help newly-freed African Americans transition into citizenship. In an era when women’s rights efforts were separating from civil rights work, women like Everett and her colleagues negotiated the tangled prejudices against gender and race in cities where local leadership often had changed little in the previous decade.

Writing to her parents from her stateroom on the SS Saratoga on November 14, 1869, a 28-year-old schoolteacher from Remson, New York remarked that “This is a good place for one to become accustomed to the new style of humanity with which I expect to become so familiar soon, for the waiter boys are all colored.”[1] Cynthia Everett, daughter of Welsh abolitionist minister and newspaperman Robert Everett, had volunteered to be a teacher for the American Missionary Association (AMA) schools and was bound for Norfolk, Virginia where she would take charge of a class of African-American boys at one of the three day schools in the city, teaching them reading, writing, math and catechism. Everett, who had been teaching for nearly a decade by the time she embarked for Norfolk, knew few African Americans and had never travelled to the south before taking the position with the AMA. She arrived in a city that was struggling to find a new way after the end of the Civil War. Occupied by the Union Army until the spring of 1870, Norfolk, like most southern cities during Reconstruction, was divided on issues of education, public services and the future of the newly free population of the city. The role of the AMA in the Norfolk school system was at the center of this struggle while Cynthia Everett was teaching, and her letters reflect the uncertainty of the future of education for black children in the city.

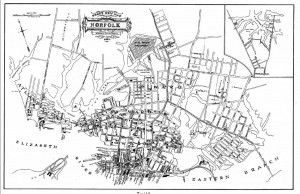

Everett and her fellow teachers worked in three schools established by the AMA. The Wilson Institute on Bute Street in downtown Norfolk was closest to the teachers’ residence, and the Southgate’s Institute and Calvert Street School were in the heart of Norfolk’s African American neighborhoods. The schools were founded during the Civil War and operated continuously from 1864 until they closed in March 1870 when the city council voted to establish public schools for black children rather than pay the American Missionary Association to keep their schools open, as they had previously agreed to do. In the six years the schools were in operation, several dozen women and a handful of men taught under the auspices of the AMA. The schools operated under Superintendent Henry C. Percy and were run out of the Wilson Institute, just down the street from the Bute Street Methodist Church. From what few accounts remain, Cynthia Everett’s experiences as a teacher were typical of the women who passed through the city while working for the AMA, although perhaps her experience was less contentious than that of many of her fellow teachers.[2]

closest to the teachers’ residence, and the Southgate’s Institute and Calvert Street School were in the heart of Norfolk’s African American neighborhoods. The schools were founded during the Civil War and operated continuously from 1864 until they closed in March 1870 when the city council voted to establish public schools for black children rather than pay the American Missionary Association to keep their schools open, as they had previously agreed to do. In the six years the schools were in operation, several dozen women and a handful of men taught under the auspices of the AMA. The schools operated under Superintendent Henry C. Percy and were run out of the Wilson Institute, just down the street from the Bute Street Methodist Church. From what few accounts remain, Cynthia Everett’s experiences as a teacher were typical of the women who passed through the city while working for the AMA, although perhaps her experience was less contentious than that of many of her fellow teachers.[2]

Cynthia Everett was born into a family of Welsh immigrants who had settled in upstate New York in the 1820s. The second youngest of eleven children, Cynthia was very close to her siblings and parents. Her father, Robert Everett, was a Congregationalist minister and editor of Y Cenhadwr Americanaidd, or The American Missionary, a Welsh language paper that circulated via the Welsh immigrant community and Welsh Congregationalist Church in the Northeast and Midwest. The entire family wrote for and helped to publish the paper, and Cynthia had been writing articles since childhood. Alongside Welsh news, religious tracts and Welsh language preservation, the paper published antislavery tracts and other reform texts, and the Everett home was a center of reform work before and during the Civil War. Cynthia made items for antislavery fairs and knit socks for soldiers during the war. Educated at Mount Holyoke Seminary, she worked as a teacher in and around the family’s hometown of Remson, New York alongside her sister Jennie. She never married, and her letters reveal evidence of an unrequited romance, which may have driven her to join the AMA to escape watching the object of her affections marry another woman.[3]

Cynthia was commissioned as a teacher to the freed people in October 1869, she spent several weeks in training in New York City and then took a steamship to Norfolk in mid-November. She roomed with one of the other teachers, Mary Rodgers, a widow from New York, who taught in the school every winter. Her early opinions of her students in both her day school classes and the Sunday Schools she taught in were guarded. She wrote to her sister Jennie who was also a teacher, “There seem always to be some in the class who have a pretty correct idea of the leading facts of the bible, while others give answers droll enough. As a whole they are more completely in ignorance than I expected to find them.”[4] Over time, her opinion of her students grew more positive and more affectionate; she found most of them eager to learn and engaged, although she often worried over the desperate poverty most of her students lived in. Her response is very similar to that of another Norfolk teacher, Sarah Stanley, one of the few black teachers in Norfolk.[5] The teachers distributed clothing, shoes, food and supplies to the students and their families as well as providing an education, and Cynthia’s letters are full of requests for extra copies of books, used clothing and other items she could use in her classroom or give to her students.[6]

Cynthia was commissioned as a teacher to the freed people in October 1869, she spent several weeks in training in New York City and then took a steamship to Norfolk in mid-November. She roomed with one of the other teachers, Mary Rodgers, a widow from New York, who taught in the school every winter. Her early opinions of her students in both her day school classes and the Sunday Schools she taught in were guarded. She wrote to her sister Jennie who was also a teacher, “There seem always to be some in the class who have a pretty correct idea of the leading facts of the bible, while others give answers droll enough. As a whole they are more completely in ignorance than I expected to find them.”[4] Over time, her opinion of her students grew more positive and more affectionate; she found most of them eager to learn and engaged, although she often worried over the desperate poverty most of her students lived in. Her response is very similar to that of another Norfolk teacher, Sarah Stanley, one of the few black teachers in Norfolk.[5] The teachers distributed clothing, shoes, food and supplies to the students and their families as well as providing an education, and Cynthia’s letters are full of requests for extra copies of books, used clothing and other items she could use in her classroom or give to her students.[6]

The Norfolk teachers found many things to entertain them once school let out at 1pm. They attended events around the city, taught Sunday school and evening adult classes, and Cynthia spent many hours exploring the city with her pupils, who were happy to bring her to meet their parents and relatives or walk the waterfront and watch the ships come in. After her first few weeks in Norfolk, Cynthia’s letters were filled with anecdotes describing the lives of Norfolk’s African American elders, many of whom she visited. She and the other teachers visited women like Mrs. Anderson, an elderly woman who had been enslaved despite her Native American ancestry and who was sold out of the city and away from her family as a child, but she managed to return after emancipation and was “sort of a teacher and prophetess among the slaves.”[7] Not all of her visits resulted in stories of resilience. One woman appealed to the missionary teachers to help her with her husband, who kept a mistress and intended to take a new wife when they moved house, as he had been expected to do under slavery.[8] Every single story Cynthia related to her family described the lingering impact of slavery on the African American population of Norfolk, from poverty, illiteracy, and a strong love of liberty and determination to succeed.

Most of the families they visited were extremely impoverished and shared accommodations with several families and they struggled to keep themselves clothed. As winter approached in Norfolk, the cold and damp prevented many students who did not have adequate clothing from coming to school. The final month of 1870 was unseasonably cold, the teachers had to wear their heavy winter clothing they had brought from the north (all of the Norfolk teachers were from New York or New England), but their students had only “shirts, pants and jackets almost too ragged to stay on them.” Distributing clothing was key function of the AMA, and a room was set aside in the school to store donations. Teachers also wrote home to ask for additional items for their students from their families and churches.[9] Luckily, by Christmas Norfolk was having a heat wave and Everett and her fellow teachers found themselves complaining of the heat and incessant rain. Handling the fluctuating temperatures and bad weather took a toll on the teachers’ wardrobes as well, and many of them relied on hiring the parents of their pupils to mend stockings, sew hoop skirt covers and otherwise keep their clothes free of wear and mud from the wet city streets.[10] Their students continued to attend school with ragged clothing and no shoes, or stay home if they were clothed too poorly to be seen in public.

While Cynthia Everett, Mary Rogers and the other teachers taught their classes and spent their weekends teaching at various Sunday Schools around the city and visiting community elders, the city council debated the future of black education in Norfolk. When the AMA first opened schools in Norfolk in 1864, they did so with the agreement that the city would support the schools once the city government was established. By 1869, the city’s public schools for white children had been reopened and the Superintendent Percy was working to broker an agreement between the city and the AMA to support the schools. The Norfolk schools were some of the most expensive to operate in the AMA’s network, as the teachers had to be both paid and their housing rented by the AMA, with no support from the city of Norfolk. Although the majority of Norfolk teachers were single, northern women and were paid relatively little, there was growing concern about the costs incurred by the schools.[11]

The city was not particularly welcoming to the northern teachers and turnover was high, which added to the overall costs.[12] Everett, like many teachers, was unwelcome in Norfolk’s white society. Within a few weeks of her arrival an article titled “Fault-Finding Females” ran in the Norfolk Journal, which seemed to call her out directly. The article remarked indignantly that, “the idea of a snow-bird-on a-an ash-bow sort of a woman trying to tell us editors how to publish a paper! It is exquisitely funny, to say the least. We would like to see her out the editorial tripod with pen in hand, and undertake to ‘run a archive’ in the daily morning line. She would soon learn that darning socks and rocking the cradle suit her and her sex much better than a life of editing or teaching editors.”[13] Everett, who had worked on her father’s newspaper along with rest of her siblings was capable of editing and the “snow bird” comment seems to strike directly at the northern teacher recently arrived in the city. The paper did not object only to interference outside the classroom, but to their methods in class as well. The Journal wrote in January 1870, that “We want good and reliable teachers, who do not harp on the nasal twang to such an extent as to teach their pupils that the people of the South have no rights that Puritanism is bound to respect. In other words, we want teachers of our own for the new element.”[14] As students were taught diction and recitation along with writing and arithmetic, they learned to speak like their northern teachers, something that would have been quite noticeable in a city with a distinctive accent of its own. Resentment over the presence of northern teachers in a city with high unemployment rates and the wounded pride of the Confederacy may have driven the city council to insist on local teachers rather than those chosen by the AMA.

Despite concerns about the teachers nosing into local business, the schools and students had gained some praise by 1869. In 1866, the Norfolk Virginian¸ a short-lived Confederate newspaper, had joyfully announced that the AMA schools would soon be closing. By the following year, and with the publication of the Norfolk Journal, which was an instrument of the Reconstruction government, the schools received a glowing report from the editor, who had attended one of the recitations put on by the students.[15] The city council took up the issue of taking on the public schools, and the two body council disagreed vehemently over how public education for Norfolk’s African American population should be organized. The city Select Council supported continuing with the AMA schools and city support, while the Common Council, led by a former Confederate, wanted the city to assume the schools and hire local teachers to staff them. The two bodies argued over what to do for over six months and multiple special committees were convened to attempt to come to a resolution. The major point of contention was the concern of the Common Council that the northern teachers would take the salaries they were paid and spend that money outside of the community whose taxes supported them. The Common Council wanted to hire Virginians to teach in the schools and to operate them as part of the existing public school system while the Select Council appropriated $4,000 that would be supplemented by additional funds by the AMA to continue operating the existing schools.[16]

Every two weeks between mid-October 1869 and January 1870, as the councils met, additional information on the meetings appeared in the papers and the teachers were told to begin packing and preparing to be sent to other cities as it appeared that Norfolk would assume full responsibility for the schools and the newly-formed Norfolk School Board would manage them along with the schools for white students. Norfolk’s teachers were particularly close, and Cynthia wrote that, “We feel like spending our moments together while we may for the Association fears it will have to withdraw from Norfolk. There has been a very great outlay of money and labor here in years past–and all just minds feel that it is high time the city awoke to its duty and interest sufficiently to help support the colored schools.”[17] From her letters, it appears in their final weeks the teachers spent most of their spare time together rather than venturing out into the city. Few accounts of walks or missionary visits to the poor, elderly or housebound were included, instead the uncertainty and deep sense of friendship between the teachers was reiterated. Perhaps some of their reticence to continue their previous patterns of behavior was due to negative attention from the white population or concern that they would be seen as abandoning their posts by their students.

The teachers’ fears were realized in March, when Cynthia Everett, Mary Rogers and the other teachers were sent to other cities. Everett wound up in Charleston, South Carolina, teaching an advanced math class to secondary schools boys. A brief history of the AMA’s efforts in Norfolk were published, and a reunion of teachers was held in 1871. Ultimately, Superintendent Percy, who was instrumental in drafting the deal for the city to take over the schools and establish a city school board, was pleased with the new system.[18]

[1] Cynthia Everett to Elizabeth Everett and Edward Everett, November 14, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[2] Norfolk was plagued with problems from white teachers protesting over sharing house with their black peers and married male teachers carrying on extramarital affairs with unmarried younger female teachers. Several works on the lives and efforts of AMA teachers have been published over the last few decades. Joe Richardson, Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1800 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988); Judith Weisenfeld, “‘Who Is Sufficient for These Things?’ Sara G. Stanley and the American Missionary Association, 1864-1868,” Church History 60, no. 4 (December 1, 1991): 493–507, doi:10.2307/3169030; Heather Andrea Williams, “‘Clothing Themselves in Intelligence’: The Freedpeople, Schooling, and Northern Teachers, 1861-1871,” The Journal of African American History 87 (2002): 372, doi:10.2307/1562471.

[3] Mary Evans to Cynthia Everett, April 6, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois. Information about the Everett family comes from the Inventory to the Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Ill. Many of the family papers are in Welsh and little scholarly attention has been paid to the family in English language publications, although several books and articles exist about them in Welsh.

[4] Cynthia Everett to Jennie Everett, November 22, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[5] Weisenfeld, “”Who Is Sufficient for These Things?,” 495.

[6] Cynthia Everett to Sarah Everett Pritchard, December 4, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[7] Cynthia Everett to Brother and Sister, December 25, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[8] Cynthia Everett to Mary Everett, January 31, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[9] Everett to Pritchard, December 4, 1869.

[10] Everett to Brother and Sister, December 25, 1869; Cynthia Everett to Elizabeth Everett, December 28, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[11] “Norfolk City Records of the Select Council,” 1869, 186, Sargent Memorial Collection, Norfolk Public Library.

[12] Weisenfeld notes that the city’s teachers fell sick regularly and were sent home in the summer to avoid unhealthy conditions. Weisenfeld, “”Who Is Sufficient for These Things?,” 495.

[13] “Fault-Finding Females,” Norfolk Journal, November 24, 1869.

[14] “Colored Public Schools,” Norfolk Journal, January 8, 1870.

[15] Both articles were reprinted in “A Contrast: Our Colored Schools in Virginia,” The American Missionary 11, no. 7 (July 1867): 151–52.

[16] “Select Council Records,” 176–194; Thomas Henson, “Colored Schools,” Norfolk Journal, December 31, 1869.

[17] Cynthia Everett to Anna Everett, January 3, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[18] Cynthia Everett to Mary Everett, March 4, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois; H. C. Percy, “History,” The American Missionary 15, no. 9 (September 1871): 197–99.

“Ply Your Needle for the Slave”: Crafts, Charity Bazaars and Sentimentalism

[This is a conference paper given at the Nineteenth Century Interdisciplinary Studies Association Conference, March 2013 and forms the basis of the article in progress.]

“When an old woman has patched a quilt, she longs to tell some of the thoughts which occupied her mind during the progress of the work.”[1]

Nineteenth-century women participated in various reform efforts not only as writers and speakers for their causes, but also as fundraisers and consumers of household goods bought and sold at charitable bazaars held to raise money for their cause. Particularly in Boston, New York and other larger northern cities and towns, bazaars were the major fundraising and social function of the anti-slavery year. Women made needlepoint samplers, wove shawls, knitted clothing and accessories, put up preserves, painted and drew touching scenes, as well as wrote poetry and prose for sale at these charity bazaars. Many of these middle-class women were accomplished artists and their enjoyment of their work is palpable in the letters they wrote accompanying these items for sale. The anti-slavery bazaars and other fundraisers of the early nineteenth century had tables overflowing with samplers, knitted goods, paintings, pottery and other handcrafted items that expressed reform sentiments and also displayed the artistic ability of middle class women who supported the cause. However, women who made goods for sale felt compelled to justify their use of their time to create the works of art they sold at the bazaars by couching the language and content of these crafts in the reform terminology of the nineteenth century. Knitting, needlepoint and other crafts were considered frivolous, unfashionable wastes of time for adult women in the early nineteenth century, unless one was making socks or other useful items for the family.[2] Donating their “ladies’ fancy work,” as one disparaging anti-slavery advocate in England called it, to charity bazaars were one way women justified practicing their crafts as adults (young, unmarried women were expected to practice arts and crafts as part of their education).

The bazaar has a long and full historiography. Beginning with F. K. Prochaska’s work in the 1970s, the charity bazaar has been examined as a locus of conflicting gender roles, women and economics, and even the word bazaar evokes the unusual, the problematic and the enticing.[3] Historians’ work on the bazaar has focused on women’s negotiation with separate spheres by claiming access to the marketplace through reform efforts and documents their success in raising money for a variety of causes in the nineteenth century. All of these historians remarked on the variety of goods women gathered and made to fill their bazaars and the poetry and short stories they filled the volumes of the Liberty Bell and other charity books with. Few historians have looked at the goods women donated as more than an example of the effort women put towards their causes, or even, as Beverly Gordon argues, as undermining their serious work of organizing and engaging in political work.[4] More recent work, including articles by Peter Gurney and Lawrence Glickman, have focused on the bazaars as part of the rise of consumer culture that came out of the reform efforts of the early nineteenth century, seeing them as the rise of consciousness that followed in the wake of industrialization.[5] All of these works position the bazaar within larger themes of rising commercialization, the negotiation of gender roles, and the reforming sentiments of the antebellum middle class, but they do not look at the ways in which those women who created the objects to be sold thought of their work and used reform efforts as an excuse to practice their craft.

Anti-slavery women had long tied their cause to the handicrafts they produced. Around 1825, the Ladies’ Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves in England sold work bags for women to carry their embroidery or knitting, emblazoned with an anti-slavery message. The card inside the work bag explained that they could carry the bag to help enlighten others on the issue of slavery. The bags were sold as a fundraiser for the Ladies’ Society, allowing them to print more anti-slavery tracts and fund schools for slaves in the West Indies.[6] These work bags were sold alongside anti-slavery tea sets from Wedgewood, and other household items emblazoned with anti-slavery logos which appealed to women in their own homes.

Perhaps the largest charity bazaar in the mid-nineteenth century was the Boston-based American Anti-slavery Society fair held every winter before Christmas at Faneuil Hall. Organized by Maria Weston Chapman and her sisters, the Boston Anti-slavery Bazaar raised funds to support anti-slavery speakers and publications as well as lawyers and lobbyists. The bazaar sold handmade goods, a magazine, The Liberty Bell, as well as items like sugar grown without slavery. The bazaar was a social event as well as a fundraiser, and the crowds were entertained by choirs singing hymns and anti-slavery songs and they snacked on baked goods and drank beverages purchased from food stands run by the American Anti-slavery Society ladies. The shoppers browsed tables filled with hand made goods in the two days leading up to Christmas Eve. These items had been stitched by anti-slavery women on both sides of the Atlantic, and the tables overflowed with embroidered samplers stitched by the daughters of prominent anti-slavery speakers, clothing, aprons, stockings, work bags, lace cuffs, shawls, reticules and purses, preserves, pies, cakes, ceramics and pottery, jewelry, and anything else that could be embellished with an anti-slavery logo or design, or made from free grown cotton or foodstuffs. The organizers called for donations in The Liberator and other major anti-slavery newspapers, asking women to “use needles in the cause of bleeding humanity.”[7] The majority of the sources for this article come from the advertisements, solicitation letters, annual reports and thank you notes sent by the organizers of and contributors to the bazaars.

The annual reports of the National Anti-Slavery Bazaar reveal the breadth of craft women (and a few men) produced in the nineteenth century. The vast majority of items sold at the bazaar (besides books) were handmade, and the lists of items that appear in the annual reports range from the expected handmade clothing and house wares like dresses, shawls, quilts and cushions to taxidermy animals, collections of seaweed and other scientific specimens, hand woven cloth, embroidered samplers, lace doilies, antimassacars (to keep hair grease and powder from one’s upholstery), aprons, afghans, hand carved trays and small pieces of furniture, toys and hand tatted lace modesty panels.[8] The variety of objects they received was astounding, and many represented traditional handcrafts from the region they were produced (woven plaids from Scotland, lacework from the Scottish isles, wool cushions from the English lowlands). The scientific collections sold were also collected by women, including a large collection of algae and seaweed collected by British women and solicited from prisoners in New Zealand and Australia.[9] When men contributed hand made goods, they tended to be woodworking or even taxidermy, hobbies or crafts that were traditionally male.[10]

Perhaps one of the most famous contributors to the bazaars was Harriet Martineau, the British travel writer and sociologist. Martineau had a troubled relationship to craft, her family was not well off, at times they were in danger of losing their home, and Martineau and her mother began working as seamstresses in order to help support their family without violating the norms of middle-class respectability, which forbid women from working outside the home for pay. Harriet became well known for the detailed embroidery she added to the pieces she sewed, and once she began making enough to live off her writing; she began embroidering antimacassars and other household items and donating them for fairs. As slavery had been outlawed in the British Empire before she was able to sew for pleasure, Martineau donated most of her items to American bazaars, and due to her popularity as an author, they were in great demand. By the late 1850s, she had sent dozens of items to bazaar organizers and worried her goods were going out of style.

After some hesitation I have sent off a parcel by Mrs Steinthal’s box for your Phila fair. The reason of my hesitation is that so much of my woolwork has gone to your country (3 pieces, altogether) & the work itself is getting so old-fashioned, I am told, among fashionable people, that the gift may not be so welcome as something newer. But I am equal to this sort of work & not to anything requiring more sight & more attention. I did intend this particular piece for my own divan, & to have worked another pattern for others’ use; but this pattern turns out (to our eyes) so exceedingly pretty that I am ashamed to keep it for myself: & so I send it to you. If it brings you any dollars, well & good. If not, & you will kindly accept a rejected bit of work, do keep it, my dear friend, in memory of me.[11]

Martineau worried that her embroidery was becoming dated by the middle of the century, but her pieces continued to draw significant sale prices and raised hundreds of dollars at antislavery bazaars. Self-depreciation was a common theme in the letters that accompanied donated handmade items. Women were concerned that their items were not good enough, fashionable enough, or not the right size.[12] For Martineau, her woolwork was a symbol of her commitment to the cause, she had once supported herself by sewing and fancy embroidery and once her writing brought in enough money to support her, she rarely sewed except for donations to charity events.[13] Clearly some of the items were a problem, as the National Anti-Slavery Bazaar began asking women not to donate certain items in their annual reports, most notably sofa cushions and children’s dresses, which they noted in the mid-1850s that they could not sell as many as were donated because everyone had bought them in previous years and they were so well made, those bought previously had not yet worn out and that it was too hard to find children the right size to fit the dresses.[14]

The annual reports also listed items that were in great demand or widely admired. Infighting amongst the various anti-slavery factions led to several letters circulating in Great Britain which claimed that money raised by the National Anti-slavery Bazaar was going to support William Lloyd Garrison and his paper The Liberator. Many more conservative anti-slavery advocates disavowed Garrison because he supported women’s rights, religious schism and disunion, and refused to support any group which supported him. The National Anti-slavery Bazaar funds did not go to Garrison directly, although they did support activities put on by the American Anti-slavery Association, of which Garrison was a director. Several women’s groups in Britain continued to support the National Bazaar, and the organizers went out of their way to thank those groups for their participation in the annual reports.

May we take the liberty of inserting here, that a handsome Highland Shawl, in which the colors are simply blue and white, would, at the next Bazaar, find a ready purchaser? Such an one has been inquired for with praiseworthy perseverance for several years, and we would gladly, by-and-by, be able to supply the demand.[15]

It becomes clear that the organizers of the bazaar appreciated the craftsmanship and beauty of the items women sent for sale, but that they also had a firm grasp on what their shoppers were looking for and what would bring in the largest donations to the organization. Items from Europe were always in demand, as they thought the crafters in Europe would always be more in fashion that those in the US. Shoppers were looking to purchase items they might not be able to find elsewhere, or to buy items they would buy anyway in a venue that would support their cause. By asking for a specific item, the organizers were not only passing on the wishes of their consuming public, but also impacting the trends in crafting, and revealing the fashion trends among American reforming women: the move towards simple dress in plain colors which distinguished middle-class women from the working class. Vibrant colors, flamboyant embroidery and busy patterns were by the middle of the nineteenth century, styles which indicated one was a member of the lower classes, where middle-class women wore simple and well-made dresses and accessories.[16]

As the bazaar organizers tried to manage the number and type of items donated, women also wrote in with and after sending their donations to discuss what the items meant to them as objects of their dedication to the cause. Letters fill the records of the bazaar organizers detailing the work that went into the items and the symbolism in them. The annual report of the Boston anti-slavery festival contains the following touching letter from Margaret Bracken of Halifax:

Whilst sitting at my work, I thought there must be as many stitches in my quilt as you have slaves in America, and … it was a simple question in multiplication, the simple result of which is, that there are about twenty times as many slaves in America as there are stitches in my quilt; and when I thought of the helpless misery endured by every individual slave through a life-time of unprotected bondage, and though of the omniscient eye of a just and holy and righteous and merciful God, who looks down alike on the oppressor and the oppressed, I cannot express the appalling sensation which comes over me.[17]

Bracken’s letter expresses doubt over the worthiness of her donations, her concern over her tardiness in thanking Chapman for the copy of the Liberty Bell she sent and then expresses the extraordinary connection she made between her own craft and the slaves she sought to help. Bracken’s quilt clearly meant more to her than a simple charity donation intended to raise money; the actual act of stitching the quilt helped her feel connected to the slaves and gave her a sense of perspective. The numerous stitches in the quilt and the careful labor she put into each one represented her emotional connection to the plight of the slaves (and also her distance from them, as they are more numerous than her stitches, they are also faceless and nameless). The items women donated to these bazaars were not simply items crafted for profit, but also a way for women to engage emotionally with the cause they supported and their work embodied their commitment as well as their pride in their efforts.

Donating items for sale to charity bazaars took on a more important meaning to women in Britain in the 1850s. As the anti-slavery movement in Britain fractured after 1840, both due to divisions in the American movement and due to lack of interest after slavery was abolished in the empire in 1833, women still committed to the cause struggled to find ways to help. As the male leadership of the largest anti-slavery organization, the British & Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, argued over whether to continue to help the more active and radical Garrisonians in America, the women were left without direction for their efforts. Many anti-slavery women’s societies in Britain wrote to the British & Foreign Anti-slavery Society asking which American associations were holding bazaars and where they should send the boxes of donated items, and heard only silence in return. Eventually, the Bristol and Clifton Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society, one of the most active in Britain, wrote directly to the Massachusetts’ Ladies Anti-slavery Society to discover if they supported radical ideas like woman’s suffrage, and discovered that they officially did not (although many members did individually). The Bristol and Clifton ladies began donating to the National Bazaar again. When anti-slavery women in Bristol, England, discovered in 1851 that some of their members had left and formed a new anti-slavery society, they realized that, “the cause of separation from us is that we aid the Boston bazaar,—that the Boston Society has connected with it some parties who hold and publish sentiments which they esteem unorthodox.”[18]

Anti-slavery bazaars served as important spaces for women to exercise their skills as salespeople, as fundraisers and to display their commitment to their cause. The items women made and donated to these fairs were more than just the products of their free time and spare change. The embroidery and clothing, art and needlework carried not only the effort of the women who opposed slavery, but also served as reminders to them of the suffering of others. As they plied their needles, they thought of those who would benefit from the money raised by the sale of the item and justified making items for sale rather than for their families or even justified spending their time on craft rather than housework or other, more direct reform efforts by connecting their efforts to alleviating the suffering of others. However, these works were not presented without agonizing over their fitness for sale, their value, changing fashions and how they stacked up against other items donated. The charity bazaar became often the only way British women were involved in anti-slavery work, besides reading and distributing anti-slavery pamphlets. Making and donating items to the bazaar did not challenge gendered roles in society in the way that writing or public speaking did, and it allowed women to take pride in their handiwork.

[1] Margaret Bracken as quoted in the Report of the twenty-fourth National Anti-Slavery Festival (Boston, 1858),17.

[2] Needlework became a sign of fashionable leisure and domesticity by the 1850s, industrialization made it unnecessary for urban middle-class women to make all of their family’s clothing by the 1830s. Making goods for oneself or one’s home as an adult became déclassé (a sign of financial instability) until becoming fashionable as a hobby in the 1850s. See Marianne van Remoortel, “Threads of Life: Matilda Marian Pullan (1819-1862), Needlework Instruction, and the Periodical Press,” Victorian Periodicals Review 45:3 (Fall 2012): 253-69 for the creation of needlework as a middle-class hobby and its design as a modish employment for an unusual historical figure; Rachel P. Maines, Hedonizing Technologies: Paths to Pleasure in Hobbies and Leisure (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009) examines the connection between growing industrialization in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and the growth of women’s leisure activities; Maria R. Miller, The Needle’s Eye: Women and Work in the Age of Revolution (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006) describes the shift of needlework as every woman’s task to the job of skilled working women in the early Republic; Steven Gelber, Hobbies: Leisure and the Culture of Work in America (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999) explains the shift of needlework from women’s work to women’s hobby in the early nineteenth century as middle-class women purchased most textiles and had servants to complete many household tasks and his own tone reflects the mid-nineteenth century sentiment that women’s handicrafts were frivolous but better than being idle; and Anne McDonald, No Idle Hands: The Social History of American Knitting (New York: Ballantine Books, 1988) documents the shifting trends and necessity of knitting socks, mittens and sweaters from the colonial era to the twentieth century. Each of these works examines the shifting meaning of leisure and craft, but none of them grapple with how women reacted to their hobbies being demeaned as frivolous and how they tried to connect the artistic hobbies they enjoyed to what society considered meaningful and appropriate work for a middle-class woman: reform.

[3] F. K. Prochaska “Charity Bazaars in Nineteenth-Century England,” The Journal of British Studies 16:2 (Spring, 1977): 62-84 is one of the earliest modern historians to examine the charity bazaar in the context of the Anglo-Atlantic reform efforts, although he sees it as a middle class appropriation of what had been a legitimate way for working-class families to supplement their income. He also sees the bazaar as problematic for middle-class women who were transgressing the lines that divided women’s appropriate sphere from the commercial world.

[4] Historians of anti-slavery women, most notably Julie Roy Jeffrey, Sandra Petrulionis, Debra Gold Hansen and Beth Salerno have examined the bazaar as an opportunity for anti-slavery women to contribute to the effort without transgressing the boundaries that public speaking required and did not require the skill as a writer that not all women possessed. Beverly Gordon, in her article, “Playing at Being Powerless: New England Ladies Fairs, 1830-1930,” The Massachusetts Review 27:1 (Spring, 1986): 144-60, argues that the frivolous nature of the items being sold undermine the real economic and political work women organizers were doing.

[5] Lawrence Glickman “’Buy for the Sake of the Slave’: Abolitionism and the Origins of American Consumer Activism,” American Quarterly 56:4 (Dec., 2004): 889-912 and Peter Gurney “’The Sublime of the Bazaar’: A Moment in the Making of a Consumer Culture in Mid-Nineteenth Century England,” Journal of Social History 40:2 (Winter, 2006): 385-405.

[6] “Card explanatory of the contents of the Society’s Work Bags” Mic 903, Friends’ Library, London.

[7] The Liberator 4:50 (Nov. 23, 1834): 187.

[8] The annual reports of the 20th through 24th National Anti-Slavery Bazaar (1854-57) contain descriptions of some of the items they received for sale, focusing particularly on the items received from Britain and Scotland as the more conservative anti-slavery organizations in Great Britain were waging a campaign against Garrison and his friends, among whom they numbered the Weston sisters, who organized the National Anti-Slavery Bazaar and wrote and published the Liberty Bell.

[9] Annual Report of the 24th National Anti-Slavery Bazaar (Boston: 1857).

[10] Women were often discouraged from engaging in hobbies that were messy or required the use of sharp tools like knives, so men were more likely to carve, make furniture or turn wood. Gelber, Hobbies, 169-70.

[11] Harriet Martineau to Lucretia Mott, October 9, 1858 in Deborah Anna Logan, ed., The Collected Letters of Harriet Martineau (London: Pickering and Chatto, 2007) 4: 124.

[12] See in addition to Martineau’s letters, SMW to Deborah Weston, 31 October 1855, Rare Books Collection, Boston Public Library, Ms.A.9.2 v.5 n.41 for a concern over too small stockings for Maggie (the letter, written from Staten Island, is probably from one of the Weston sisters or nieces who was living with Maria Weston Chapman)

[13] See Deborah Anna Logan, The Hour and the Woman (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2002).

[14] Report of the twentieth National Anti-Slavery Bazaar (Boston, 1854), 11 and Report of the twenty-first National Anti-Slavery Bazaar (Boston, 1855), 8. Samuel May Anti-Slavery Collection, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

[15] Report of the twentieth National Anti-slavery Bazaar (Boston, Mass 1854), 10-11. Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection, Cornell University Libraries.

[16] See Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986); Mary Ryan, Cradle of the Middle Class (Boston: Cambridge University Press, 1981); Maria R. Miller, The Needle’s Eye: Women and Work in the Age of Revolution (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2006); and for Britain, Leonora Davidoff and Catherine Hall, Family Fortunes (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1987) for discussions of middle-class dress and propriety. Many anti-slavery women were Quakers, which meant that anti-slavery women’s groups were particularly somber in their dress, particularly in the mid-Atlantic.

[17] Report of the twenty-fourth National Anti-Slavery Festival (Boston, 1858), 16-17.

[18] Statements respecting the American Abolitionists; by their opponents and their Friends indicating the present struggle between Slavery and Freedom in the United States of America (Dublin: 1852), 15.

Recent Comments