“The Cause of Education Here”: Cynthia Everett and the American Missionary Association Schools in Norfolk, VA

This paper is a draft and may not be distributed in any form without the permission of the author. Thanks to Rhiannon Williams, University of South Wales for information on the Everett family, Louis Humphrey for his assistance in transcribing Cynthia Everett’s papers, and Troy Valos and the staff of the Sargent Collection, Norfolk Public Library for their aid in locating the schools run by the AMA in Norfolk.

In 1869, a 28-year-old schoolteacher from upstate New York was sent by the American Missionary Association to Norfolk, VA to teach for the schools established for African American children after the Civil War. Although from a family that had strongly supported antislavery efforts before the war, Cynthia Everett had had little exposure to African American culture or southern society before her move to Norfolk in the fall of 1869. She spent most of two years in Norfolk and Charleston, SC, and her letters reveal the details of daily life in Reconstruction-era southern cities and the negotiations over the role of northern, white women in the leadership of local school systems and the networks of charitable organizations which tried to help newly-freed African Americans transition into citizenship. In an era when women’s rights efforts were separating from civil rights work, women like Everett and her colleagues negotiated the tangled prejudices against gender and race in cities where local leadership often had changed little in the previous decade.

Writing to her parents from her stateroom on the SS Saratoga on November 14, 1869, a 28-year-old schoolteacher from Remson, New York remarked that “This is a good place for one to become accustomed to the new style of humanity with which I expect to become so familiar soon, for the waiter boys are all colored.”[1] Cynthia Everett, daughter of Welsh abolitionist minister and newspaperman Robert Everett, had volunteered to be a teacher for the American Missionary Association (AMA) schools and was bound for Norfolk, Virginia where she would take charge of a class of African-American boys at one of the three day schools in the city, teaching them reading, writing, math and catechism. Everett, who had been teaching for nearly a decade by the time she embarked for Norfolk, knew few African Americans and had never travelled to the south before taking the position with the AMA. She arrived in a city that was struggling to find a new way after the end of the Civil War. Occupied by the Union Army until the spring of 1870, Norfolk, like most southern cities during Reconstruction, was divided on issues of education, public services and the future of the newly free population of the city. The role of the AMA in the Norfolk school system was at the center of this struggle while Cynthia Everett was teaching, and her letters reflect the uncertainty of the future of education for black children in the city.

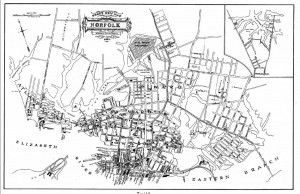

Everett and her fellow teachers worked in three schools established by the AMA. The Wilson Institute on Bute Street in downtown Norfolk was closest to the teachers’ residence, and the Southgate’s Institute and Calvert Street School were in the heart of Norfolk’s African American neighborhoods. The schools were founded during the Civil War and operated continuously from 1864 until they closed in March 1870 when the city council voted to establish public schools for black children rather than pay the American Missionary Association to keep their schools open, as they had previously agreed to do. In the six years the schools were in operation, several dozen women and a handful of men taught under the auspices of the AMA. The schools operated under Superintendent Henry C. Percy and were run out of the Wilson Institute, just down the street from the Bute Street Methodist Church. From what few accounts remain, Cynthia Everett’s experiences as a teacher were typical of the women who passed through the city while working for the AMA, although perhaps her experience was less contentious than that of many of her fellow teachers.[2]

closest to the teachers’ residence, and the Southgate’s Institute and Calvert Street School were in the heart of Norfolk’s African American neighborhoods. The schools were founded during the Civil War and operated continuously from 1864 until they closed in March 1870 when the city council voted to establish public schools for black children rather than pay the American Missionary Association to keep their schools open, as they had previously agreed to do. In the six years the schools were in operation, several dozen women and a handful of men taught under the auspices of the AMA. The schools operated under Superintendent Henry C. Percy and were run out of the Wilson Institute, just down the street from the Bute Street Methodist Church. From what few accounts remain, Cynthia Everett’s experiences as a teacher were typical of the women who passed through the city while working for the AMA, although perhaps her experience was less contentious than that of many of her fellow teachers.[2]

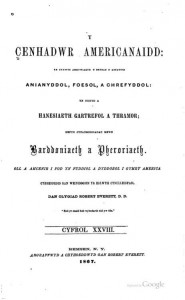

Cynthia Everett was born into a family of Welsh immigrants who had settled in upstate New York in the 1820s. The second youngest of eleven children, Cynthia was very close to her siblings and parents. Her father, Robert Everett, was a Congregationalist minister and editor of Y Cenhadwr Americanaidd, or The American Missionary, a Welsh language paper that circulated via the Welsh immigrant community and Welsh Congregationalist Church in the Northeast and Midwest. The entire family wrote for and helped to publish the paper, and Cynthia had been writing articles since childhood. Alongside Welsh news, religious tracts and Welsh language preservation, the paper published antislavery tracts and other reform texts, and the Everett home was a center of reform work before and during the Civil War. Cynthia made items for antislavery fairs and knit socks for soldiers during the war. Educated at Mount Holyoke Seminary, she worked as a teacher in and around the family’s hometown of Remson, New York alongside her sister Jennie. She never married, and her letters reveal evidence of an unrequited romance, which may have driven her to join the AMA to escape watching the object of her affections marry another woman.[3]

Cynthia was commissioned as a teacher to the freed people in October 1869, she spent several weeks in training in New York City and then took a steamship to Norfolk in mid-November. She roomed with one of the other teachers, Mary Rodgers, a widow from New York, who taught in the school every winter. Her early opinions of her students in both her day school classes and the Sunday Schools she taught in were guarded. She wrote to her sister Jennie who was also a teacher, “There seem always to be some in the class who have a pretty correct idea of the leading facts of the bible, while others give answers droll enough. As a whole they are more completely in ignorance than I expected to find them.”[4] Over time, her opinion of her students grew more positive and more affectionate; she found most of them eager to learn and engaged, although she often worried over the desperate poverty most of her students lived in. Her response is very similar to that of another Norfolk teacher, Sarah Stanley, one of the few black teachers in Norfolk.[5] The teachers distributed clothing, shoes, food and supplies to the students and their families as well as providing an education, and Cynthia’s letters are full of requests for extra copies of books, used clothing and other items she could use in her classroom or give to her students.[6]

Cynthia was commissioned as a teacher to the freed people in October 1869, she spent several weeks in training in New York City and then took a steamship to Norfolk in mid-November. She roomed with one of the other teachers, Mary Rodgers, a widow from New York, who taught in the school every winter. Her early opinions of her students in both her day school classes and the Sunday Schools she taught in were guarded. She wrote to her sister Jennie who was also a teacher, “There seem always to be some in the class who have a pretty correct idea of the leading facts of the bible, while others give answers droll enough. As a whole they are more completely in ignorance than I expected to find them.”[4] Over time, her opinion of her students grew more positive and more affectionate; she found most of them eager to learn and engaged, although she often worried over the desperate poverty most of her students lived in. Her response is very similar to that of another Norfolk teacher, Sarah Stanley, one of the few black teachers in Norfolk.[5] The teachers distributed clothing, shoes, food and supplies to the students and their families as well as providing an education, and Cynthia’s letters are full of requests for extra copies of books, used clothing and other items she could use in her classroom or give to her students.[6]

The Norfolk teachers found many things to entertain them once school let out at 1pm. They attended events around the city, taught Sunday school and evening adult classes, and Cynthia spent many hours exploring the city with her pupils, who were happy to bring her to meet their parents and relatives or walk the waterfront and watch the ships come in. After her first few weeks in Norfolk, Cynthia’s letters were filled with anecdotes describing the lives of Norfolk’s African American elders, many of whom she visited. She and the other teachers visited women like Mrs. Anderson, an elderly woman who had been enslaved despite her Native American ancestry and who was sold out of the city and away from her family as a child, but she managed to return after emancipation and was “sort of a teacher and prophetess among the slaves.”[7] Not all of her visits resulted in stories of resilience. One woman appealed to the missionary teachers to help her with her husband, who kept a mistress and intended to take a new wife when they moved house, as he had been expected to do under slavery.[8] Every single story Cynthia related to her family described the lingering impact of slavery on the African American population of Norfolk, from poverty, illiteracy, and a strong love of liberty and determination to succeed.

Most of the families they visited were extremely impoverished and shared accommodations with several families and they struggled to keep themselves clothed. As winter approached in Norfolk, the cold and damp prevented many students who did not have adequate clothing from coming to school. The final month of 1870 was unseasonably cold, the teachers had to wear their heavy winter clothing they had brought from the north (all of the Norfolk teachers were from New York or New England), but their students had only “shirts, pants and jackets almost too ragged to stay on them.” Distributing clothing was key function of the AMA, and a room was set aside in the school to store donations. Teachers also wrote home to ask for additional items for their students from their families and churches.[9] Luckily, by Christmas Norfolk was having a heat wave and Everett and her fellow teachers found themselves complaining of the heat and incessant rain. Handling the fluctuating temperatures and bad weather took a toll on the teachers’ wardrobes as well, and many of them relied on hiring the parents of their pupils to mend stockings, sew hoop skirt covers and otherwise keep their clothes free of wear and mud from the wet city streets.[10] Their students continued to attend school with ragged clothing and no shoes, or stay home if they were clothed too poorly to be seen in public.

While Cynthia Everett, Mary Rogers and the other teachers taught their classes and spent their weekends teaching at various Sunday Schools around the city and visiting community elders, the city council debated the future of black education in Norfolk. When the AMA first opened schools in Norfolk in 1864, they did so with the agreement that the city would support the schools once the city government was established. By 1869, the city’s public schools for white children had been reopened and the Superintendent Percy was working to broker an agreement between the city and the AMA to support the schools. The Norfolk schools were some of the most expensive to operate in the AMA’s network, as the teachers had to be both paid and their housing rented by the AMA, with no support from the city of Norfolk. Although the majority of Norfolk teachers were single, northern women and were paid relatively little, there was growing concern about the costs incurred by the schools.[11]

The city was not particularly welcoming to the northern teachers and turnover was high, which added to the overall costs.[12] Everett, like many teachers, was unwelcome in Norfolk’s white society. Within a few weeks of her arrival an article titled “Fault-Finding Females” ran in the Norfolk Journal, which seemed to call her out directly. The article remarked indignantly that, “the idea of a snow-bird-on a-an ash-bow sort of a woman trying to tell us editors how to publish a paper! It is exquisitely funny, to say the least. We would like to see her out the editorial tripod with pen in hand, and undertake to ‘run a archive’ in the daily morning line. She would soon learn that darning socks and rocking the cradle suit her and her sex much better than a life of editing or teaching editors.”[13] Everett, who had worked on her father’s newspaper along with rest of her siblings was capable of editing and the “snow bird” comment seems to strike directly at the northern teacher recently arrived in the city. The paper did not object only to interference outside the classroom, but to their methods in class as well. The Journal wrote in January 1870, that “We want good and reliable teachers, who do not harp on the nasal twang to such an extent as to teach their pupils that the people of the South have no rights that Puritanism is bound to respect. In other words, we want teachers of our own for the new element.”[14] As students were taught diction and recitation along with writing and arithmetic, they learned to speak like their northern teachers, something that would have been quite noticeable in a city with a distinctive accent of its own. Resentment over the presence of northern teachers in a city with high unemployment rates and the wounded pride of the Confederacy may have driven the city council to insist on local teachers rather than those chosen by the AMA.

Despite concerns about the teachers nosing into local business, the schools and students had gained some praise by 1869. In 1866, the Norfolk Virginian¸ a short-lived Confederate newspaper, had joyfully announced that the AMA schools would soon be closing. By the following year, and with the publication of the Norfolk Journal, which was an instrument of the Reconstruction government, the schools received a glowing report from the editor, who had attended one of the recitations put on by the students.[15] The city council took up the issue of taking on the public schools, and the two body council disagreed vehemently over how public education for Norfolk’s African American population should be organized. The city Select Council supported continuing with the AMA schools and city support, while the Common Council, led by a former Confederate, wanted the city to assume the schools and hire local teachers to staff them. The two bodies argued over what to do for over six months and multiple special committees were convened to attempt to come to a resolution. The major point of contention was the concern of the Common Council that the northern teachers would take the salaries they were paid and spend that money outside of the community whose taxes supported them. The Common Council wanted to hire Virginians to teach in the schools and to operate them as part of the existing public school system while the Select Council appropriated $4,000 that would be supplemented by additional funds by the AMA to continue operating the existing schools.[16]

Every two weeks between mid-October 1869 and January 1870, as the councils met, additional information on the meetings appeared in the papers and the teachers were told to begin packing and preparing to be sent to other cities as it appeared that Norfolk would assume full responsibility for the schools and the newly-formed Norfolk School Board would manage them along with the schools for white students. Norfolk’s teachers were particularly close, and Cynthia wrote that, “We feel like spending our moments together while we may for the Association fears it will have to withdraw from Norfolk. There has been a very great outlay of money and labor here in years past–and all just minds feel that it is high time the city awoke to its duty and interest sufficiently to help support the colored schools.”[17] From her letters, it appears in their final weeks the teachers spent most of their spare time together rather than venturing out into the city. Few accounts of walks or missionary visits to the poor, elderly or housebound were included, instead the uncertainty and deep sense of friendship between the teachers was reiterated. Perhaps some of their reticence to continue their previous patterns of behavior was due to negative attention from the white population or concern that they would be seen as abandoning their posts by their students.

The teachers’ fears were realized in March, when Cynthia Everett, Mary Rogers and the other teachers were sent to other cities. Everett wound up in Charleston, South Carolina, teaching an advanced math class to secondary schools boys. A brief history of the AMA’s efforts in Norfolk were published, and a reunion of teachers was held in 1871. Ultimately, Superintendent Percy, who was instrumental in drafting the deal for the city to take over the schools and establish a city school board, was pleased with the new system.[18]

[1] Cynthia Everett to Elizabeth Everett and Edward Everett, November 14, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[2] Norfolk was plagued with problems from white teachers protesting over sharing house with their black peers and married male teachers carrying on extramarital affairs with unmarried younger female teachers. Several works on the lives and efforts of AMA teachers have been published over the last few decades. Joe Richardson, Christian Reconstruction: The American Missionary Association and Southern Blacks, 1861-1800 (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1988); Judith Weisenfeld, “‘Who Is Sufficient for These Things?’ Sara G. Stanley and the American Missionary Association, 1864-1868,” Church History 60, no. 4 (December 1, 1991): 493–507, doi:10.2307/3169030; Heather Andrea Williams, “‘Clothing Themselves in Intelligence’: The Freedpeople, Schooling, and Northern Teachers, 1861-1871,” The Journal of African American History 87 (2002): 372, doi:10.2307/1562471.

[3] Mary Evans to Cynthia Everett, April 6, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois. Information about the Everett family comes from the Inventory to the Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Ill. Many of the family papers are in Welsh and little scholarly attention has been paid to the family in English language publications, although several books and articles exist about them in Welsh.

[4] Cynthia Everett to Jennie Everett, November 22, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[5] Weisenfeld, “”Who Is Sufficient for These Things?,” 495.

[6] Cynthia Everett to Sarah Everett Pritchard, December 4, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[7] Cynthia Everett to Brother and Sister, December 25, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[8] Cynthia Everett to Mary Everett, January 31, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[9] Everett to Pritchard, December 4, 1869.

[10] Everett to Brother and Sister, December 25, 1869; Cynthia Everett to Elizabeth Everett, December 28, 1869, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[11] “Norfolk City Records of the Select Council,” 1869, 186, Sargent Memorial Collection, Norfolk Public Library.

[12] Weisenfeld notes that the city’s teachers fell sick regularly and were sent home in the summer to avoid unhealthy conditions. Weisenfeld, “”Who Is Sufficient for These Things?,” 495.

[13] “Fault-Finding Females,” Norfolk Journal, November 24, 1869.

[14] “Colored Public Schools,” Norfolk Journal, January 8, 1870.

[15] Both articles were reprinted in “A Contrast: Our Colored Schools in Virginia,” The American Missionary 11, no. 7 (July 1867): 151–52.

[16] “Select Council Records,” 176–194; Thomas Henson, “Colored Schools,” Norfolk Journal, December 31, 1869.

[17] Cynthia Everett to Anna Everett, January 3, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois.

[18] Cynthia Everett to Mary Everett, March 4, 1870, Everett Family Papers, Newberry Library, Chicago, Illinois; H. C. Percy, “History,” The American Missionary 15, no. 9 (September 1871): 197–99.

Recent Comments